Comment on inflation expectations, uncertainty, the Phillips curve, and monetary policy by Christopher Sims

Comment by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s 53rd Annual Economic Conference

Chatham, Massachusetts, 10 June 2008

It is a pleasure to be here to discuss Chris’s paper. The paper gives us a view of the history of the Phillips curve stressing the role of inflation expectations. Chris talks about the usefulness of the Phillips curve concept, with a focus on the "new" Keynesian Phillips curve, for analysing price determination. He pretty much concludes that it is not particularly useful, preferring instead to talk about inflation determination without a Phillips curve. He then examines departures from rational expectations and the implications of new ideas about expectations formation for monetary policy, building on the critique of what Tom Sargent has termed the "communism" of rational expectations(1).

Why the emphasis on inflation expectations and the Phillips curve? Why do we have a whole session on it at this conference? The reason is because the Phillips curve has been at the core of thinking about macroeconomic stabilisation for as long as macroeconomics has existed---indeed much before Phillips’s paper. As early as the 1920s, for example, academics and policy researchers at the Federal Reserve were talking in terms of concepts that today we identify with the Phillips curve(2).

There are two central elements for understanding inflation in the Phillips curve framework. One is the concept of economic slack (the output gap) and the other is inflation expectations. Both elements are unobservable and potentially problematic, subject to misunderstanding and misuse. Regarding the output gap in particular, we are so ignorant about its proper definition and measurement in real time that it leaves little, if any, room for it to be useful for policy(3). So when we think about the Phillips curve, inflation expectations must be at the center of policy considerations.

Why are inflation expectations so important? To begin with, inflation expectations are a crucial determinant of actual price and wage setting and, therefore, actual inflation over time. In the Phillips curve context, this is the case regardless of what one may think the proper measure of the output gap may be. Well-anchored inflation expectations are essential not only for securing price stability, but also for facilitating overall economic stability over time. As we know, when private inflation expectations become unmoored from the central bank’s objective---episodes characterised by Marvin Goodfriend (1993) as "inflation scares"---macroeconomic stabilisation can suffer. With unanchored inflation expectations, the Phillips curve becomes too unpredictable to be a useful concept for policy guidance.

Well-anchored inflation expectations are arguably most important during times that may be most challenging for monetary policy---such as what we are going through at present. In such times, two things are useful to keep in mind. One is that monetary policy can have considerably greater leeway in responding to adverse supply shocks when inflation expectations are well-anchored. This can be easily understood in the context of Phillips curve analysis. The other is that the central bank can also have greater flexibility for swift responses to financial disturbances if it can be confident that inflation expectations will remain well-anchored. I think we’ve seen this in practice since last August 2007, again and again.

So what about the importance of inflation expectations under the present circumstances? We need only look at very recent statements about monetary policy by the ECB and the Federal Reserve to appreciate the central role policymakers attach to them. Consider the introductory statement read by ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet at the press conference following the Governing Council’s monetary policy decision meeting last week: "Against this background, it is imperative to secure that medium to longer-term inflation expectations remain firmly anchored in line with price stability" (Trichet, 2008). And compare this with what I thought was a key sentence from yesterday’s dinner speech by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke: "The Federal Open Market Committee will strongly resist an erosion of longer-term inflation expectations, as an unanchoring of those expectations would be destabilising for growth as well as for inflation" (Bernanke, 2008). When comparing the two statements it is clear that well-anchored inflation expectations is the underlying thinking in both central banks.

Despite the central role of inflation expectations in the Phillips curve and the emphasis policy practitioners place on them, most of the Phillips curve models we have seen in the last fifty years rely on rather simplistic and unrealistic models of inflation expectations. Two examples serve as useful illustrations of this simplicity and lack of realism. In the early days of Phillips curve modeling, we had the linear fixed-distributed-lag models, and later the rational expectations models under perfect knowledge. At present the traditional modeling still, by and large, imposes rational expectations in a world with fixed and perfectly known structures, including known and stable policy preferences. As Jim Stock reminded us this morning, this is really equivalent in some sense to the old-fashioned modeling of expectations, which was incorrectly called "adaptive expectations" back in the 1950s and 1960s. I say "incorrectly" because nothing adapted in these models---parameters were kept fixed, by assumption. Under these assumptions using either the old-fashioned distributed-lag models or the new, more modern if you wish, linear rational expectations models, the monetary policy problem is rather trivial and anchoring inflation expectations is a simple matter of policy adopting and adhering to a stable policy rule.

By downplaying the information limitations that either policymakers or economic agents likely face in reality and oversimplifying the expectations formation mechanism, both "old" and "new" Phillips curve models have some common issues. They may suggest, for example, that a Phillips curve model should be able to forecast inflation better than is likely achievable in practice. They may also suggest the existence of an exploitable short-run tradeoff between price stability and economic stability. This may raise hopes among academics, and perhaps even among some policymakers, about what monetary policy might be able to achieve. Indeed, one should be concerned that, if misused, these models could lead both forecasters and policymakers astray. This is an issue I hope Chris will elaborate further in the context of his model.

I fully agree with Chris that it is useful to deviate from the assumption of rational expectations in Phillips curve models and to think a little bit more about learning and alternative models of expectations formation. Recent work has explored various avenues for improving the expectations formation mechanisms embedded in Phillips curve models making them more useful for policy analysis. A common element in these models that I wish to stress is the acknowledgement of the presence of "imperfections" in the formation of expectations, relative to the simplistic rational expectations model we continue to use as the benchmark model. As a result, these models can better capture the inherent limitations in gathering and processing information. One way of proceeding has been to posit that private agents may act as econometricians. I have in mind here an exercise along the lines of Stock and Watson (1999) who consider re-specifying and re-estimating forecasting models with the objective of obtaining in an adaptive manner the best forecast they can with available data. Why do they posit that the forecaster should respecify and reestimate the model in order to achieve this? Because they are concerned about structural change and uncertainty, imperfections that influence expectations formation in practice.

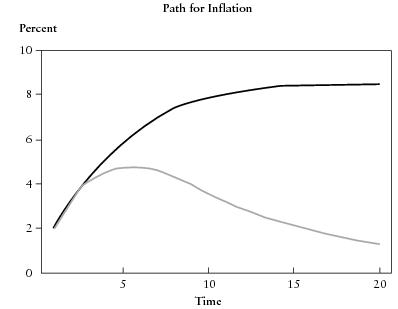

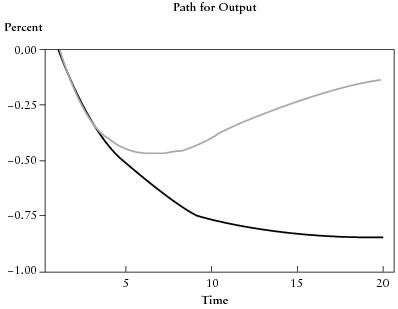

To illustrate the implications of alternative treatments of expectations, I will present to you a simple example, reproduced from earlier work with John C. Williams (Orphanides and Williams, 2005). Consider two economies with an identical Phillips curve and the same monetary policy rule. One treatment assumes that expectations are always well-anchored, the rational expectations outcome based on perfect knowledge. In the alternative treatment, agents learn from recent economic outcomes in forming expectations. One way to interpret the experiment is to compare these two models and analyse the impact of an adverse supply shock to the economy. In other words, assess whether second-round effects from an adverse supply shock can be avoided, as we would say on the other side of the Atlantic. If so, then the impact of the adverse supply shock can be avoided and everything appears to be perfect. Otherwise, if these effects cannot be avoided, the economy may experience conditions that bring back memories of stagflation. In the figure, the grey lines show what a supply shock would look like with well-anchored inflation expectations. We have a temporary hump in inflation and a mild slowdown in the economy. Yet in the case of unanchored inflation expectations, where expectations are formed with a learning mechanism, as the black lines show, second-round effects on inflation follow the original supply disturbance which, if unchecked, lead to a protracted stagflationary episode.

This deviation from the simple linear rational expectations paradigm has a number of implications. Learning behaviour in the formation of expectations introduces non-linear dynamics in otherwise linear economies. Specifically, it induces time-variation in the formation of expectations, and hence in the structure of the economy, even in the absence of fundamental regime changes. This complicates empirical modeling, including estimation and forecasting of what might otherwise be a fixed-coefficient linear model. I note that all these issues arise in this environment simply because of the presence of an imperfection in expectations formation.

Even more interesting are the implications for monetary policy. Learning behaviour in the formation of expectations may impart additional persistence to inflation for a given monetary policy, thereby diminishing the policymaker’s ability to stabilise business cycle fluctuations in addition to maintaining price stability. This provides an explanation as to why the appearance of an exploitable policy tradeoff in an estimated linear rational expectations Phillips curve model is unlikely to be useful in practice. Furthermore, perpetual learning with imperfect knowledge induces the endogenous "inflation scares" that can be particularly damaging to the economy without a forceful policy response. This provides an explanation why policymakers monitor inflation expectations so closely and place a premium on maintaining well-anchored inflation expectations.

There are also implications for policy communication. Recognition of the role of learning in the formation of expectations introduces a role for central bank communication that is absent in traditional models. To the extent that central bank communication can facilitate the formation of more accurate inflation expectations, it can prove useful for improving policy outcomes. In this light, clarity regarding the central bank’s price stability objective may improve macroeconomic performance.

In summary, properly accounting for the formation of inflation expectations is essential for understanding the potential usefulness and inherent limitations of Phillips curve models. One may love or one may hate these models, but I think much of the difference in perspective comes from improper or from better accounting of how expectations are assumed to be formed in these models. Many of the puzzles which seem to be associated with Phillips curves could potentially be solved once we recognise the richness introduced by deviating from the old-fashioned fixed-coefficient–distributed-lag models or the new, but still old-fashioned, linear rational expectations models of the Phillips curve. New approaches that incorporate learning may better capture the formation of inflation expectations, and I think we can make a lot of progress by moving in this direction without completely throwing away the intellectual framework of the Phillips curve. Nonetheless, some of the pertinent lessons may be quite simple. First, clarity regarding the central bank’s price stability objective may facilitate efforts to maintain well-behaved inflation expectations, even in the presence of a series of adverse shocks. And second, maintaining well-anchored inflation expectations over time enhances the central bank’s ability to flexibly respond to financial disturbances as well as adverse supply shocks.

-------------------------------------------------------------

ENDNOTES:

(1) See Evans and Honkapohja (2005).

(2) See Orphanides (2003) for references to early 1920s versions of the Phillips curve and their relation to the modern policy debate.

(3) See Orphanides and van Norden (2005) for an empirical examination of the problems associated with real-time inflation forecasts based on output gaps.

REFERENCES:

Bernanke, Ben S. (2008) "Outstanding issues in the analysis of inflation", paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s 53rd Annual Economic Conference, Chatham, Massachusetts, 9 June.

Evans, George and Seppo Honkapohja (2005) "An interview with Thomas J. Sargent", Macroeconomic Dynamics, 9(4): 561-583.

Goodfriend, Marvin (1993) "Interest rate policy and the inflation scare problem: 1979-1992", Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, 79(1): 1-23.

Orphanides, Athanasios (2003) "Historical monetary policy analysis and the Taylor Rule", Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(5): 983-1022.

Orphanides, Athanasios and Simon van Norden (2005) "The reliability of inflation forecasts based on output gap estimates in real time", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 37(3): 583-601.

Orphanides, Athanasios and John C. Williams (2005) "Imperfect knowledge, inflation expectations, and monetary policy", in B. S. Bernanke and M. Woodford (eds) The Inflation-Targeting Debate, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stock, James H. and Mark W. Watson (1999) "Forecasting inflation", Journal of Monetary Economics, 44(2): 293-335.

Trichet, Jean-Claude (2008) "Introductory statement", Monetary Policy Decision Meeting, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, 5 June.

Figure: Evolution of economy following an adverse supply stock

Reproduced from Orphanides and Williams (2005)

Notes:

Grey line — with well-anchored inflation expectations

Black line — with unanchored inflation expectations