Policy challenges in the euro area

Wrap-up panel discussion by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, at the BIS Research Conference on "Central Bank Balance Sheets in Asia and the Pacific: The Policy Challenges Ahead" organised by the Bank of Thailand

Chiang Mai, 13 December 2011

When I arrived in this beautiful setting, for which I want to thank the organizers, some people suggested that this must be a respite from thinking about the euro area. There was a point to that, perhaps. But it was then suggested to me that maybe we should talk a little more about the present difficulties in the euro area at this conference, so why don’t I focus my comments on that.

With respect to the broader topic of the conference, it should be noted that in the euro area we have been pursuing balance sheet policies at the ECB which are not qualitatively different from those pursued by the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. As elsewhere, these policies have succeeded in significantly lowering interest rates, as reflected, for instance, in government yields perceived to be nearly risk free.

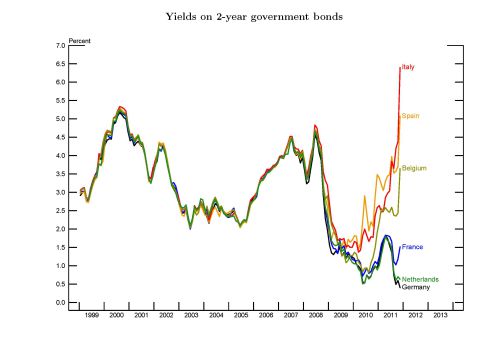

But that is not the issue. The issue is that the major problem we are facing right now and that is having an impact on the rest of the world, is that the euro area is not a single country and the government debt of a number of member states is no longer perceived to be nearly risk free. Following the creation of the ECB and the single monetary policy in 1999, the euro area did indeed behave as a common currency area where the single monetary policy was transmitted in pretty much the same way in all member states. As of 2009, however, this, increasingly, no longer works. This can be easily seen by plotting the two-year government yields for different countries in the euro area. By plotting the two year yield, we can focus on a rate that is closely associated with the transmission of monetary policy in macro models.

The chart plots the yields of the six largest member states of the euro area that make up almost 90% of the economy. What can be observed in the last couple of years is a divergence in yields suggesting increasing problems with the ability of the single monetary policy to function properly. Note that Greece, Portugal and Ireland are not included in this chart. That is, the chart does not include the countries that have experienced such severe difficulties that they have had to ask for assistance from the IMF and their European Union partners.

Let me briefly provide you with my take on the problem and the steps towards a solution. Let's start with some fundamentals. For a currency union to function properly, some minimal fiscal policy coordination is necessary. This can occur with a fiscal union, which in the European Union, we decided not to have. The European Union treaty prohibits member states from assuming the debts of other member states and prohibits monetary financing by any central bank in all member states.

The alternative approach that was adopted is to try to have strict limits on debts and deficits. This was the idea behind the Stability and Growth Pact. The idea was to have such a tight control of fiscal policy in each individual member state, that no member state would run into trouble. Indeed, in order to avoid any moral hazard issues, no crisis management mechanism was set up at the beginning. It was assumed that the strict fiscal rules and the absence of any crisis management mechanism would be sufficient to avoid any country getting into trouble.

Unfortunately, the fiscal framework was not properly enforced. In addition, the market discipline that might have worked to help limit large deficits in countries with a large debt did not work, because prior to the crisis every member state was able to finance their deficits at virtually the same rate―there was no differentiation. During the crisis in 2009, it became clear that some member states–Greece is the most important example–had been running deficits that were too large and were not limiting the size of their debt. So the question was: once this was observed in 2009, how could the problem be solved?

It was no longer feasible to say we could not have a crisis mechanism in place―one now had to be created in a hurry. Then two things happened in the spring of 2010. First, a makeshift mechanism to help Greece by providing it with loans was set up. The second was to create the EFSF as the temporary crisis management mechanism. But the problem was how to provide help in a way that would avoid moral hazard in the future.

Here I want to focus on two choices. The first choice would have been to focus on strengthening prevention and credible enforcement. Specifically, introduce even stricter fiscal rules or constitutional amendments for balanced budgets and consider limiting the sovereignty of member states that misbehave to ensure compliance. The second choice was to raise the cost a country would face during a crisis. The first approach was not chosen in 2010 because some of the decision-making countries did not want to tighten the rules and did not want to limit their own sovereignty. So the second approach was chosen―raise significantly the costs of handling a crisis, including the present one.

This was a very critical decision. Throughout 2010, and since then, there have been discussions about whether one way to enforce better discipline would be to introduce the concept of private sector involvement (PSI) in euro area debt. The concept was that an investor buying euro area sovereign debt would have to worry that if the country misbehaved, then a haircut on the debt would be implied, even if there was no issue regarding the sustainability of the debt. Following its adoption in October 2010, this approach proved quite effective in raising the cost of financing of any country that was perceived as facing a potential difficulty. Unfortunately, it was quite damaging and it was probably a key factor behind the difficulties faced by Ireland and Portugal in the few months after its introduction.

Surely, the idea of introducing PSI in euro area sovereign debt markets was to raise the cost of a crisis for the country involved and serve as a deterrent, helping countries avoid getting into trouble. However, it wasn’t such a good idea to introduce PSI during the current crisis. Even worse were two decisions taken this year, the first on 21 July and the second on 26 October, to impose haircuts on Greek debt. I will not dwell on whether Greek debt was sustainable or not. As discussed in an earlier presentation, this assessment is sensitive to the underlying assumptions and is subject to great uncertainty. What is certain is that creating the precedent that a member of the euro area would be forced to impose a haircut on the holders of its debt reinforced to investors how the PSI concept would be applied in the euro area. This is very costly. As can be seen in the chart, following the first decision on 21 July that suggested a small haircut the spreads of Spain and Italy rose. Following the second decision on 26 October that raised the size of the Greek haircut, the spreads of Belgium and France rose.

The chart shows clearly the resulting problem. Once the political decision was taken to impose haircuts on one country, international investors had to allow for the possibility that sometime in the future, haircuts would be imposed on other countries. As a result, a large number of the euro area member states are now considered much less trustworthy than before the PSI decisions and face higher costs of financing.

So where do we go from here? First, a positive note. The damage created by the PSI decisions seems to have been understood. A major U-turn was observed in last week’s meeting of the European heads of state. The notion that private sector involvement should be expected with higher frequency for those who purchased euro area debt is now recognized as damaging and there is an effort to remove it from the framework that is being built for the future. There is essentially an effort to go back to the alternative choice I mentioned earlier that was not made in 2010.

Instead of raising the costs of solving a liquidity crisis when that occurs, this backpedaling is taking us to the other alternative, that of prevention and credible enforcement. A very important step that was agreed last week is the agreement that, going forward, all euro area governments will impose stricter rules on themselves by adopting balanced budget amendments in their constitutions. And there is a discussion on limiting sovereignty as an enforcement device. We are going to see in the coming weeks how this will be implemented.

With this in place, and if this indeed goes on as projected in the coming weeks, then the second element could be discussed perhaps by the next meeting of the heads of state. And that would be to find more reasonable ways to provide liquidity, helping a country that is under market threat. This is something that we haven’t touched upon yet. Here I want to note that although the EFSF was created last year and a permanent stabilization fund is planned, by limiting the size of resources that can be made available during a crisis we have failed to convince the markets that sufficient resources would be available in case countries such as Italy or Spain face difficulties. Since the decisions that improve the governance framework and protect against moral hazard have been taken, we now need to improve the crisis management framework so that potentially unlimited backing is available from governments to other governments, if needed.

I leave you with a question. A lot of analysts around the world are looking at the EFSF and saying to the ECB, isn’t that your job? And the answer is no: the ECB is the lender of last resort to the banking system, it cannot serve as a lender of last resort to governments. What we have here is a fiscal governance issue that our governments need to solve. Once the political solutions are provided, once we have the appropriate framework at the political level, then and only then can we solve this problem convincingly.