The role of central banks: lessons from the crisis

Panel remarks by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, at the Banque de France international symposium on "Which regulation for global imbalances?"

Paris, 4 March 2011

The topic of this session is lessons from the crisis, specifically regarding the role of central banks. Let me start with a question: How do we learn in our profession? The answer, I believe, is that our main guide is history. Indeed, one of the many differences between central banking and the natural sciences is that in central banking, unlike the natural sciences, we cannot run controlled experiments to improve our knowledge. As a result of the crisis, we are experiencing a unique natural experiment to draw lessons from. I fully expect this episode, which unfortunately is still mutating and evolving in some areas, to provide material for myriads of PhD theses and other studies for decades to come.

What do we mean by ‘lessons’ for the role of central banks? Lessons in the sense of learning things we did not know? Or in the sense of reaffirming things we knew? In my view, we have some of each but, in addition, we have seen an evolution in the consensus views on familiar questions. Let me focus on just a few(1).

***

The crisis has reaffirmed the benefits of an independent central bank focused on maintaining price stability and safeguarding well-anchored inflation expectations in line with price stability. The focus on price stability yields gains in credibility and allows central bank flexibility as well as the ability to act decisively when needed on other issues. As an example, let me remind you of the decisive provision of liquidity in August 2007 and later in September 2008. Another example is the decisive policy easing in response to the crisis. The risks of deflation were greatly reduced because inflation expectations over the medium term remained well-anchored, in line with our definition of price stability(2). The new spike in energy prices, that reminds us of the spectre of stagflation risks, once again reaffirms how important it is to act decisively to ensure that inflation expectations remain well-anchored to preserve stability.

***

Another lesson reaffirmed is that monetary policy is not just about setting policy rates. Even though the academic consensus was converging to this view before the crisis, monetary policy is not just about determining current and future overnight interest rates. As both practical experience and also earlier generations of academics have taught us, there is much more to monetary policy.

Prior to the crisis, some were concerned about the zero bound on short-term nominal rates. However, the large array of unconventional measures employed successfully by various central banks around the world to engineer further policy easing has dispelled the fear that the zero bound is like hitting a wall, rendering monetary policy helpless.

The management of a central bank’s balance sheet has been understood as an important policy tool. We have also learned, in some cases while forced to innovate on the way, about operational aspects that matter for policy. Examples include the collateral framework and the list of counterparties. In revised editions of central banking textbooks, I expect to find discussions of these things that were absent from the pre-crisis editions.

***

Τhere have also been lessons about the strategy of monetary policy. In my view, the crisis has reaffirmed the danger associated with the temptation to fine tune the real economy, in addition to maintaining price stability. One way to pose this debate is by contrasting two views.

The first, the stability oriented approach, can be characterised as attempting to dampen economic fluctuations by promoting stable economic growth over time, subject to the primary focus on price stability.

The second, the activist view, can be seen as suggesting that, in addition to price stability, an equally important goal of monetary policy is to actively guide the economy towards attainment of its ‘potential.’ That is, an important guide to policy is the ‘output gap’, which measures how far GDP deviates from its potential. But policy activism in this sense can be dangerous. Trying too hard to close real activity gaps can lead to worse results in both price stability and economic stability. The reason is simple. Too often, the measures of the output gap that our experts can produce give the wrong signal in real time, when policymakers need to take decisions.

Distracting attention away from price stability by attempting to fine tune the real-economy might result in a central bank remaining too accommodative for too long following a recession. There are numerous examples of policy recommendations that have proved to be wrong for this reason, and not just from the 1970s. This risk must be avoided.

Nothing should distract a central bank’s focus on preserving price stability. A central bank should strive to remain focused and be pre-emptive in its fight against inflation.

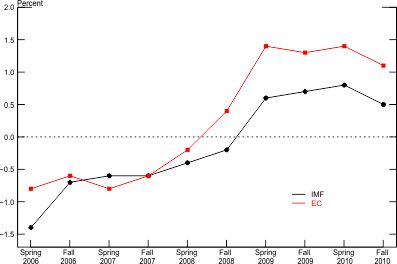

How activist central banks can be is an issue where there seems to be quite a bit of disagreement so let me be more explicit by using the euro area as an example. Let us take the first ten years of the euro area and look at real-time estimates of the output gap as published by the IMF and by the European Commission (EC). (The information can conveniently be found on their websites.) Both organisations have suggested, virtually every spring since 1999, that the output gap for the year reported would be negative. If we compare these to recent retrospective estimates we observe a significant bias. The bias is mainly due to the fact that the experts are now more pessimistic about what potential output was in the euro area than they were in the past. This is not the experts’ fault. We simply cannot know in real time. And this applies not only to the size of the output gap, but even to its sign. In comparing what the experts tell us now and what they were telling us then, in real time, the sign of the output gap is revealed to be incorrect in more than half of the years in the first decade of the euro area.

Consider the year 2006, the year before the financial turmoil began. According to the IMF and the EC, the euro area operated below its potential that year with the gap being around minus 1 percent (see Figure 1). As late as 2008, the year 2006 was still being seen as one of wasted resources. But by 2009, with revised estimates, the experts were telling us that three years earlier the euro area was overheated and output exceeded its potential by a significant amount.

Mismeasurement of the output gap can lead to errors not only in monetary policy—if and when central banks incorrectly rely on this information—but can also lead to mistakes in fiscal policy. In 2006 we had a fiscal deficit in the euro area as a whole. Alarms about fiscal soundness should have sounded before the crisis. But the alarms would have sounded much louder if the EC, the IMF and others had not suggested that the economy was running below potential. Inappropriate reliance on mismeasured output gaps can lead to complacency during good times.

I recount this example about how the output gap can be misused in policy debates because once again, as we are coming out of the crisis, some voices are stressing the extent of the output gap that the euro area is facing today, perhaps drawing conclusions about policy that could again be reversed as time goes by.

The focus on price stability must remain unrelenting.

***

That said, another lesson is the following: the central bank focus on price stability is insufficient to maintain overall stability in the economy. The crisis has confirmed that a central bank with a price stability objective and insufficient regulatory powers cannot ensure broader financial stability in the economy.

The crisis has revealed a general underappreciation of systemic risks in micro-prudential supervision. It has highlighted the need for a more system-wide macro-prudential approach towards supervisory oversight to ensure overall stability in the financial system. As a result, we see a shift in emphasis with new organisations created in some jurisdictions to address this gap. In the euro area, the establishment of the European Systemic Risk Board is meant to serve this role.

By definition, micro-prudential supervisors focus on individual institutions and cannot effectively assess the broader macroeconomic risks that pose a threat to the financial system as a whole. This is a task best suited to central banks. But for central banks to better enhance financial stability they must be provided with the right tools. Consider, for example, an episode of persistently high credit growth in an environment of price stability. Adjusting the interest rate tool is unlikely to be the most appropriate response. Ideally, under such circumstances, the central bank should have at its disposal, either directly or through its participation in a macro-prudential body, the macro-prudential levers with which to contain the risk of a potential financial disturbance. These could comprise the power to vary capital requirements, leverage ratios, loan-to-value ratios, margin requirements and so forth. Considering the important informational synergies between micro-prudential supervision and systemic risk analysis, bringing micro-supervision close to, if not under the same roof as, other central bank functions seems an attractive proposition. This should contribute to better management of overall economic stability.

A concern has been expressed that an expanded role by central banks in this direction could compromise their independence that is so critical in defending their primary objective of price stability. That may indeed be a risk. But precisely because central banks are generally among the most independent institutions, they can strengthen the independence of the supervisory environment. The risk of political pressure delaying a needed tightening in credit conditions via macro-prudential tools, for example, can be minimised if the central bank has a key role. In my view, this benefit, together with the benefit of informational synergies, outweigh the risks.

***

I close with a very old lesson for central banks: humility. This crisis was not just a once-in-a-generation crisis. It proved to be much worse. I hope subsequent relative calm allows our 22nd century counterparts to characterise this as a once-in-a-century event. But central banks must not let their guard down. The next crisis might well challenge the limits of our knowledge in new and as yet unknown ways.

---------------------------------------------------

ENDNOTES:

(1) I would like to note that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect views of my colleagues on the Governing Council of the European Central Bank.

(2) See also the instructive analysis by John C. Williams, the newly appointed President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, who has examined the role of well-anchored inflation expectations for containing deflation risks in the US (Williams, 2009).

RΕFERENCES:

Williams, John C. (2009) "The risk of deflation", FRB San Francisco Economic Letter, 12, 27 March.

FIGURE 1: Evolution of Output Gap Estimates for 2006

Note: IMF estimates are from the World Economic Outlook, as published in the spring and fall of each year. European Commission (EC) estimates are from the Economic Forecast, as published in the spring and autumn of each year.