Strengthening economic governance in the euro area

Remarks by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, at the Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt conference on "Macroeconomic modeling and policy analysis after the global financial crisis"

Frankfurt, 15 December 2010

It is a pleasure to be invited to speak at this conference on macroeconomic modelling and policy analysis. When we build macro models of an economy for monetary policy analysis, we typically take the institutional structure and economic governance for granted. We also tend to take it for granted that the economy we model is sufficiently integrated so that we can abstract from regional heterogeneities and can safely assume that the monetary policy transmission works in more or less the same manner in all regions. Macro models for the euro area, as for other economies, typically assume not only one common monetary policy rate for all member states of the economic and monetary union, but also a common term structure of interest rates, common financing conditions faced by consumers and firms throughout the union, and so on. Indeed, this was not an unreasonable approximation for the first decade of the euro. Government yields across member states moved together and differed little from each other(1). However, this was in an environment of stability in the economic and monetary union that has been severely challenged by the unfolding sovereign crisis. During 2010, yields on long-term government debt of euro-area member states have diverged to a degree not seen since before the birth of the euro. Tensions in sovereign debt markets have hampered the monetary transmission mechanism in the euro area to such an extent that the Governing Council of the European Central Bank decided to take exceptional measures to address them(2). The tensions that led to these extraordinary monetary policy decisions were caused by fault lines in the economic governance of the euro area that were exposed by the crisis and threatened the stability of the common currency. With this in mind, today I will discuss some issues regarding the economic governance of the euro area, and how the existing framework could be strengthened. Before I proceed, I would like to note that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of my colleagues on the Governing Council of the European Central Bank.

***

Let us first examine what went wrong. The smooth functioning of a monetary union presupposes a minimum degree of coordination of fiscal policy. Indeed, as noted in the Delors Report in 1989 about what was to become the euro area:

"[A]n economic and monetary union could only operate on the basis of mutually consistent and sound behaviour by governments and other economic agents in all member states. In particular, uncoordinated and divergent national budgetary policies would undermine monetary stability and generate imbalances in the real and financial sectors of the Community" (Delors, 1989, p. 19).

In theory, the coordination needed for fiscal policy can be achieved in two different ways. The monetary union could be supplemented by some degree of centralisation of fiscal policy. This, however, would suggest a bigger step towards a political union than the member states of the European Union deemed desirable when the economic and monetary union was formed. Alternatively, the minimum degree of coordination could be achieved by strict budgetary rules on member states ensuring that excessive budget deficits are avoided so that the stability of the currency is not threatened. In the euro area, this was the role of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The preventive arm of the SGP was supposed to provide guidance to member states to prevent excessive deficits. But in case excessive deficits materialised, the corrective arm was meant to induce a reversal so that the excessive deficit would not persist.

It did not work. First, euro area governments did not exhibit sufficient discipline to stay within the bounds of the original SGP. Second, there was a failure in budgetary reporting and surveillance. Third, there was a failure in enforcing the commonly agreed rules. In part, the failure could be attributed to the weakening of the SGP’s corrective arm in 2005 following the leadership of Germany and France. But already before the weakening of the SGP in 2005, it had been recognised that the Pact had not succeeded in restraining excessive deficits as was desired (Papademos, 2005). Simply, the rules were not enforceable and peer pressure proved insufficient to nudge governments to consistently behave responsibly.

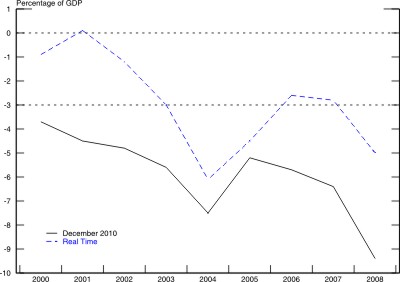

It was not only that effective sanctions were not available. Not even the extent of fiscal profligacy could be accurately assessed by European bodies. Indeed, arguably the most shocking revelation during the crisis about the failure of the SGP was the size and persistence of misreporting of fiscal balances by successive Greek governments. I am not talking just about the year 2009 for which the European Commission forecast in the spring of that year was 5.1 percent, this spring was reported at 13.6 percent, and is now estimated at 15.4 percent. Take the previous years from 2000 on. Figure 2 contrasts the latest Eurostat estimates for the deficit to GDP ratio from 2000 to 2008 with real-time estimates, specifically the estimates published by the European Commission each spring following the year in question based on data supplied by the Greek Government at the time. As can be seen, whereas in real time it appeared that in some years the deficit was below the 3 percent limit—in one year there was even a small surplus—we now know that the deficit exceeded the 3 percent limit in every single year during this period. Indeed, on average, the actual deficit—as we now know—was three percentage points larger than its real-time reporting. These misreported deficits added up to a dangerous level of debt precipitating the crisis we experienced last spring.

Could market forces have exerted the necessary budgetary discipline better than the supposed rules? This was also contemplated by the Delors Report:

"To some extent market forces can exert a disciplinary influence. However, experience suggests that market perceptions do not provide strong and compelling signals and that access to a large capital market may for some time even facilitate the financing of economic imbalances. The constraints imposed by market forces might either be too slow and weak or too sudden and disruptive" (Delors, 1989, p. 20).

Indeed, until before the crisis, relatively little differentiation was made among the debt of different governments in the euro area. The implied probability that a government would be placed in such difficulty that a negative credit event would be contemplated was extremely small. In Greece, 10-year government bond yields fluctuated within 4½ and 5? percent from the summer of 2007 to the summer of 2009 and then rose sharply from about 4½ percent in August 2009 to a high of 12.4 percent on 7 May 2010. I note that they remain high, recently trading between 11 and 12 percent. As contemplated by the Delors report, for too long market forces did not provide strong signals of trouble and subsequently overreacted, causing severe disruption. At the moment, despite a massive coordinated package by the IMF and EU, financial prices suggest significant odds on restructuring of the Greek debt. They also suggest surprisingly high odds for a number of other member states—unthinkable before the crisis.

The demonstration that in the European Union a member state can misreport its debt and deficits figures for some time is certainly one reason for this unfortunate development. The reputational damage of such deliberate misreporting by a euro area government is hard to quantify, but is surely significant. Another factor is the observation that a very deep recession, such as the one Europe experienced in 2008-09, can lead to a sharp and persistent increase in government debts creating pressure for fiscal consolidation that may be politically difficult to implement.

But member states in the euro area now seem to be also penalised for being part of the common currency area, penalised for not having the flexibility to allow their currency to contribute to macroeconomic adjustment that appears needed in some cases. This has become even more acute in recent months, despite evidence that the recession has ended and most member states’ economies have registered growth in the last few quarters.

The economic governance of the euro area must be corrected to reverse these trends and restore confidence. Indeed, this has been and continues to be part of an urgent debate by European Union bodies in recent months. The urgency is evidenced by the statement by the Eurogroup on Sunday, 28 November, indicating the agreement to set up a European Stability Mechanism (ESM)(3).

***

I believe that an important reason for the doubts now implicitly expressed about the euro area is a perception of a failure in European solidarity. We all recognise that as the social and economic ties of the member states get stronger, especially so in the euro area where we share a common currency, our fates become increasingly interconnected, our interests largely common. This calls for greater cooperation and coordination by member states, especially in the euro area. But the process of reaching agreements on the handling of the sovereign crisis in the euro area over the past several months has raised questions regarding solidarity among member states. It has also raised questions about trust among governments. Many object to suggestions of mutual support among euro-area member states because they want to avoid the EU becoming a so-called transfer union, where financial assistance is transferred from one state to another.

In my view this concern is misplaced. It is surely true that greater centralisation of fiscal policy would be one way to arrange for mutual support and that such an arrangement could perhaps take the EU partly in the direction of a transfer union. However, the euro area need not become a transfer union to allow for greater cohesion and solidarity. Demonstration of mutual support during a crisis, on the basis of clear ex ante agreed rules, does not imply a transfer union. Mutual support requires a mechanism for mutual macroeconomic stability insurance among the member states of the euro area.

Imagine if here in Germany someone told you that car insurance is verboten and that you cannot insure your brand new German car because in the event of it being damaged the insurance reimbursement would constitute an unacceptable transfer. Would banning all insurance be a sensible method for ensuring personal responsibility?

The role of stability insurance is to protect a member state against an idiosyncratic shock that might otherwise create doubts about its ability to honour debt obligations in the future and unnecessarily raise its financing costs for a long time. On their own, each member state faces some risk of this nature, but to a large extent such risks can be pooled by an insurance mechanism thus eliminating idiosyncratic risks. The insurance in this case would entail making loans available to a member state that risks a sudden halt in market refinancing. Loans are not gifts, and an insurance mechanism is not a transfer union.

Another way to look at the institutional design question is as follows. What is the institutional framework that would minimise the total cost of debt financing in the euro area? A framework that fails to pool together idiosyncratic risks as mutual insurance among the member states certainly is not the most efficient. The availability of insurance is less important for the largest members of the euro area that already pool many idiosyncratic risks internally due to their size than it is to smaller member states. That said, a well-designed mutual stability insurance among euro area member states would increase the level of confidence in the whole area. Indeed, I believe that prior to the crisis, markets implicitly assumed that by joining the euro area a member state was protected by such a mutual insurance arrangement. During the crisis, doubts regarding European solidarity have been harmful to the euro area, especially to the weakest member states.

As with any insurance mechanism design, the avoidance of moral hazard is crucial for its success. This brings us back to the flaws identified in the workings of the SGP so far. Critical improvements are essential to avoid the moral hazard problem and reap the benefits of a mutual insurance mechanism. To begin with, improved reporting of data by member states and more effective surveillance are needed. Some states already have solid mechanisms and cross-checks. Others have weaker internal institutions that may be prone to political interference and should urgently be strengthened. Setting up an independent budget evaluation agency could provide a cross-check to the budget authority of each member state and greatly improve the reporting of budgetary data and analysis to EU bodies and other euro area governments. Such an authority could report directly to the parliament of the member state so that its reports could be independently assessed and compared to the government’s budget proposals during parliamentary hearings. Greater transparency and consistency can also be achieved by adopting a multi-year fiscal planning horizon in budget discussions and incorporating extra-budgetary items, including contingent liabilities, such as unfunded future pensions. Leaving such items out of budget discussions and debt and deficit analysis inhibits dealing with them in a coherent manner. At a European level, surveillance could become more effective if the powers of Eurostat were enhanced so that it could check in greater detail the quality of reported data. In addition, an independent EU-wide fiscal agency could be mandated to scrutinise fiscal projections by member countries, with intrusive investigations in cases where there are debt or deficit concerns. A further step could be the adoption of stronger fiscal rules setting limits on the growth of expenditures as a way to secure the necessary budget consolidation in case of excessive deficit or debt ratios.

Without proper incentives to ensure that it is respected, no framework, however well designed, can be effective. For this reason, the development of a credible enforcement mechanism is an indispensable element of improving euro area governance. Proper incentives could come in the form of clear, automatic sanctions for misbehaviour by a member state. Ex ante agreement and quasi-automaticity are essential to eliminate the political impediment that would arise from an ex post application of the Council’s discretion. In addition, to encourage continuous compliance, sanctions should be meaningful and should be applied relatively early. They could include financial sanctions, such as reduced access to EU funds, but in my view should also include political sanctions, such as a limitation or suspension of voting rights. Ultimately, sanctions should be designed so as to provide the proper incentives to political authorities in member states to respect the rules of the common currency area. They must have teeth.

At this point someone could ponder how to deal with a euro area member state that does not wish to bind itself to such sanctions. Personally, I would be concerned that in such a case, the potential of moral hazard involving that member state would remain, and thus this state would not constitute an acceptable insurance risk. If the lowest common denominator on what current political authorities found acceptable were adopted, the resulting insurance mechanism would be less than ideal, requiring stronger conditionality and more stringent terms. Perhaps a better solution to the political quandary that might arise in such a situation is for euro area member states to self select into those willing to adopt strict rules and sanctions and those not willing to do so. Any member state that wishes to join a well designed mutual stability insurance mechanism would have to voluntarily agree to the adoption of strong fiscal rules and meaningful sanctions. Political authorities unable to bind their successors, for example with appropriate constitutional amendments in the member state, would self select not to join such a mechanism.

Some of the improvements in governance and the setting up of a clear mutual stability insurance mechanism may require a limited change in the Treaty. Others could be pursued even without changing the Treaty. Indeed, the new Treaty provides a framework within which to improve the workings of the euro area. I note, in particular, the new wide-ranging provision in Article 136 of the new Treaty that is specific to the euro area. It states that: "In order to ensure the proper functioning of economic and monetary union, … , [the Council] shall adopt measures specific to those Member States whose currency is the euro: (a) to strengthen the coordination and surveillance of their budgetary discipline; (b) to set out economic guidelines for them …" (European Commission, 2010b, p.106).

***

I end with two questions. First, why the urgency? Why talk about crisis management and the future of euro area economic governance now? Imagine a fire marshal in the middle of fighting a large fire. When everybody is trying to put out the fire, it would not seem the most appropriate time to talk about how to reorganise the fire department. Yet, in this instance, the intensity of fire today depends on decisions about the future that are taken today—financial markets are forward looking. Accordingly, the discussion of the European Council at its meeting over the next two days is of particular importance. Decisions fostering incentives for disciplined fiscal policies and protecting against moral hazard can contribute to safeguarding financial stability in the euro area.

Finally, one may ask why we should be so preoccupied with solidarity. Ultimately, this is what the European Union is about. Let me remind you about Article 3 of the Treaty which lays down the objectives of the Union: The article starts by noting "The Union's aim is to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples" and goes on to reaffirm that: "It shall promote economic, social and territorial cohesion and solidarity among Member States" (European Commission, 2010a, p.17). What would our Union be about without solidarity during difficult times?

------------------------------------------------

ENDNOTES:

(1) Compare, for example, the 2-year government bond yields for Greece and Germany shown in Figure 1.

(2) See European Central Bank (2010).

(3) See Eurogroup (2010).

REFERENCES:

Delors, Jacques (1989) Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the European Community, Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union, European Commission, 17 April.

Eurogroup (2010) "Statement by the Eurogroup", 28 November.

European Central Bank (2010) "ECB decides on measures to address severe tensions in financial markets", press release, 10 May.

European Commission (2010a) Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union, Official Journal of the European Union, C83, 30 March.

European Commission (2010b) Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Official Journal of the European Union, C83, 30 March.

Papademos, Lucas D. (2005) "The political economy of the reformed Stability and Growth Pact: implications for fiscal and monetary policy", speech at ‘The ECB and Its Watchers’ conference, Frankfurt am Main, 3 June.

FIGURE 1: Two-Year Government Bond Yields

Note: Monthly averages of daily observations.

FIGURE 2: Government Deficit for Greece

Note: The December 2010 series is the latest available from Eurostat. The real-time series shows, in each year, the estimate for that year reported in the European Commission forecasts published in the spring of the following year.