Central bank policy challenges in the crisis

Remarks by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, at the conference on "Financial Interdependence in the World’s Post-Crisis Capital Markets", organised by the Global Interdependence Center and the Banque de France

Paris, 17 June 2010

As crises always do, the global financial crisis we have been experiencing has brought to the forefront a number of policy challenges. It has confirmed the importance of central banks’ focus on price stability, but has also highlighted that maintaining price stability is not enough to ensure financial stability. Indeed, the crisis has brought to the fore the need for central banks to improve their contributions toward attaining financial stability in order to help with overall economic stability.

The recent intensification of tensions in Europe over the past few weeks, highlighted by the very strained sovereign debt positions of several peripheral European countries and renewed tensions in segments of the financial sector, including some government securities and money markets, has also highlighted that insufficient progress has been made since the beginning of the crisis towards making the financial system in Europe more robust. This suggests that it is imperative to make fast progress towards strengthening financial stability in Europe.

In these remarks I want to focus mainly on two sets of challenges. First, I will talk about the challenges faced over the past three years regarding the maintenance of price stability in an environment where the economy is buffeted by extreme shocks, and the role of unconventional monetary policy to meet these challenges. And second, I will discuss some of the challenges associated with improving the framework for financial stability going forward. Before I proceed, I should note that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect views of my colleagues on the Governing Council of the ECB.

Monetary policy challenges

The euro area macro economy has faced two very different sets of extreme shocks that presented a policy challenge over the past three years. The first was an inflationary threat, an adverse supply shock, associated to a large extent with a sharp increase in energy costs and the prices of other key commodities. Let me remind you that the acceleration of oil prices from the beginning of 2007 until the summer of 2008 was so dramatic as to bring back bad memories from the 1970s, specifically the painful experience we associate with the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979. Inflation briefly exceeded 4 percent in the euro area for the first time in the history of the Eurosystem. Subsequently, though, this inflationary threat subsided and indeed we have experienced a reversal of much of the earlier increase in energy costs over the past year.

And it was the second challenge that proved far more threatening for the worldwide economy. What began with the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the United States and appeared at first in the second part of 2007 to be a manageable turbulence in money and financial markets, evolved over a number of months into a global financial crisis reaching its climax in September 2008. By the end of 2008 the financial headwinds, coupled with a collapse in confidence, culminated in a dramatic drop in aggregate demand and world trade. The threat of a protracted deflationary slump loomed large, evoking comparisons with the Great Depression of the 1930s. The events following the collapse of Lehman in the United States in September 2008, had a severe adverse effect on confidence worldwide, and evolved into a synchronized severe economic downturn, causing an unprecedented collapse in industrial production and world trade. For a number of months there were concerns about a developing adverse feedback loop with the financial disturbance and a worsening real economy reinforcing each other in a downward spiral for a time. As a consequence of the reversal of the oil price shock mentioned earlier as well as the recession following the financial crisis, inflation fell and for the first time in its history the euro area experienced negative inflation readings for a few months. Inflation is now back in positive territory and closer to the ECB’s definition of price stability, but core inflation remains on the low side.

With the onset of the financial crisis and its intensification during 2008, the primary policy challenge for central banks was to preserve price stability. Beginning in September 2008, the ECB took prompt and decisive action cutting its key policy interest rate in a series of steps from 4,25% to 1% by May 2009 and embarking on a policy of fully accommodating banks’ liquidity needs. The easier monetary policies of the ECB helped to avert a plunge of the European economy into a serious deflationary downturn reminiscent of the early 1930s. Although actual movements in the HICP showed great volatility owing to sharp swings in energy and non-oil commodity prices, core inflation was kept in line with the ECB’s price stability objectives.

In this respect the ECB’s clear institutional framework for the conduct of monetary policy – whereby an independent ECB pursues a mandated specific price stability target – contributed to the continued good performance of the ECB in meeting its primary policy objective of achieving and maintaining price stability. In achieving its goal or definition of price stability, that is a rate of increase of the HICP close to but below 2 percent, the ECB had established credibility on the soundness of its monetary policy and had demonstrated its commitment to price stability.

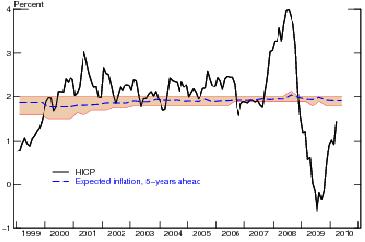

In addition, the ECB’s policy of having a clear definition of price stability, while at the same time having a forward-looking policy orientation with an associated monitoring of economic projections and, in particular, paying close attention to inflation forecasts and expectations has proved very effective for anchoring inflation expectations, at levels compatible with price stability. Monitoring short-term inflation expectations is especially valuable because expectations are an important determinant of actual price and wage setting behaviour and thus actual inflation over time. Indeed, well-anchored inflation expectations played a stabilising role at a time when the euro-area economy was under stress from destabilising financial developments and when monetary stimulus policies were required. Throughout the crisis longer-term inflation expectations remained very well anchored and in line with the ECB’s definition of price stability. This can be seen in Figure 1, reproduced from Orphanides (2010), that plots HICP inflation as well as the long-term expectations regarding inflation from the ECB's quarterly Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). As can be seen, the average of the SPF responses (the blue dashed line) has consistently been in line with the ECB's price stability mandate. This stability in expectations was observed despite the wide fluctuations in actual inflation over the past three years. There are differences of opinion among the survey respondents that are also informative. The thin red lines in the figure show the 25th and 75th percentiles of the cross-sectional distribution of responses in each quarter. As can be seen by the fairly narrow width of the shaded area, disagreement, as measured by the interquartile range of responses, has been limited, confirming the ECB’s success in anchoring inflation expectations in this extreme environment.

By mid-2009 the ECB along with other central banks around the world, including the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England had, since the last quarter of 2008, reduced interest rates to or near historical lows and, as a result, considerations on the zero bound on nominal interest rates became pertinent for monetary policy. With policy interest rates approaching or reaching historically low levels, there was the additional challenge of averting the threat of a deflationary slump by undertaking unconventional policies. In this situation, unconventional policy measures, operating through expanding or changing the composition of the central bank balance sheet, were required to effect additional monetary policy easing.

Accordingly, as nominal interest rates approached very low levels the ECB introduced its policy of "enhanced credit support", including widening the range of assets eligible as collateral by banks, providing as much liquidity as demanded with a fixed rate full allotment procedure and lengthening the maturity of liquidity operations, to enhance the flow of credit above and beyond what could be achieved through policy interest rate reductions alone. Under its menu of "non-standard" measures the ECB also introduced a programme of purchasing covered bonds and, more recently, a Securities Markets Programme that allowed the ECB to intervene in dysfunctional markets so as to help ease tensions and enhance the transmission of monetary policy.

Some of these purchases of assets by the ECB over the past two years may be viewed as examples of unusual actions and border on fiscal policy. However, such actions were simply taken either to repair market functioning or, in light of the zero bound, to engineer further monetary policy easing and defend against deflation, or both.

These unconventional or " non-standard" measures proved to be effective owing in no small measure to the credibility built-up in ordinary times by an independent bank firmly committed to price stability that enabled it to act with greater flexibility that otherwise would have risked fuelling inflationary fears. Indeed, the massive injections of liquidity by the ECB during the current crisis would not have occurred without generating great inflation fears by the public if the ECB had not established its price stability credentials, including its ability to maintain well-anchored inflation expectations. Indeed, Figure 1 shows that despite the injection of very large amounts of liquidity into the economy inflation expectations were kept in check.

It can be concluded that the ECB’s monetary policy during the current crisis has met its primary policy challenge of maintaining price stability. Furthermore, the ECB with its strong price stability credentials and well-anchored inflation expectations was able to deploy successfully non-conventional monetary measures at the zero nominal interest rate bound not only to combat the threat of deflation, but also to support the economy and to help towards easing tensions in dysfunctional markets.

Financial stability challenges

The crisis has confirmed that a central bank with a price stability objective but with insufficient regulatory powers cannot ensure broader financial stability in the economy. Without the right tools, a central bank cannot effectively deal with problems stemming from asset price misalignments and extending into other suspected financial imbalances in the economy such as overextended households and businesses, high levels of private and public debt and highly leveraged positions in finance. Perhaps the most significant challenge ahead of us is how to improve the architecture of financial supervision and provide central banks with the appropriate tools so as to better contribute to the maintenance of financial stability.

This is not to say that monetary policy has no role in tackling financial imbalances. In view of the large costs of the ongoing financial crisis, which could be related to suspected asset price misalignments, for example in housing markets, the role of monetary policy in dealing with potential asset price misalignments is very much under discussion.

As is well known, the traditional approach to this challenge has been a non-activist strategy focussing attention on the total risks to the outlook for inflation and real economic activity in evaluating policy alternatives. Interest rate policy adjustments are only called for to the extent that changes in asset prices might affect prospective output and inflation prospects over the pertinent horizon. This contrasts with a more activist approach advocating that monetary policy should "lean against the wind" of emerging financial imbalances over and above the implicit policy reaction suggested by the effect of the suspected asset price developments on the evaluation of the risks to the outlook for inflation and real economic activity. That is, "extra action" is called for to account for asset price movements to temper emerging financial imbalances and to reduce the probability of costly financial instability in the future.

But the activist approach raises a number of practical concerns. What is the magnitude of the interest rate increase required to deflate the identified bubble? What is the appropriate direction and timing of the monetary response to the suspected asset price misalignments? Should policy tighten to arrest a brewing bubble or ease in anticipation of its crash? And can asset price misalignments be identified with sufficient accuracy in real time, pre-supposing that policymakers can accurately determine the fundamental value of assets when markets fail to do so?

The "non-activist" approach does not ignore suspected asset price misalignments in the setting of interest rates if its risk evaluation frameworks are sufficiently encompassing. Indeed, the ECB’s framework may be characterised in this manner. Because asset price booms are often associated with rapid money and credit expansion, accounting for the longer-term risks reflected in the ECB’s monitoring analysis provides an appropriate framework for incorporating the pertinent information in formulating policy.

If an adjustment in interest rates can reduce the tail risks to price stability associated with a suspected price misalignment at a more distant horizon, without significantly raising risks of deviating from price stability over nearer horizons, such an adjustment would seem warranted. That said, the interest rate does not seem to be the most appropriate instrument for minimising the tail risks associated with a possible asset market collapse at distant horizons.

But given that the interest rate level may not be the best policy instrument to deal with problems relating to financial instability, what should policymakers, including central bankers, do? A compelling answer is that regulatory tools should be deployed to minimise the risks associated with suspected asset price misalignment and related emerging financial imbalances. And this raises the question regarding the scope of central bank involvement in prudential regulation and supervision.

The crisis has demonstrated a general underappreciation of systemic risks in micro-prudential supervision and highlighted the need for a more system-wide macro-prudential approach towards supervisory oversight to ensure overall stability in the financial system. By definition, micro-prudential supervisors focus on individual institutions and cannot effectively assess the broader macroeconomic risks that pose a threat to the financial system as a whole. This is a task best suited to central banks.

However, for central banks to better enhance financial stability they must be provided with the right tools. In general, a central bank does not face a trade-off between price stability and financial stability but there may be occasions when interest rate policy directed at preserving price stability is clearly insufficient to reduce risks to financial stability, such as persistently high credit growth in an environment of price stability. Adjusting the interest rate tool is unlikely to be the most appropriate response. Ideally, under such circumstances, the central bank should have at its disposal macro-prudential levers with which to contain the risk of a potential financial disturbance. These could comprise the power to vary capital requirements, leverage ratios, loan-to-value ratios, margin requirements and so forth.

The crisis has revealed weaknesses in supervisory and regulatory frameworks for addressing financial stability issues and in central bank liquidity management while at the same time exposing weaknesses in national and international crisis management frameworks. In fact, gaps in crisis management frameworks led in a few cases to the prolonged involvement of central banks in unfamiliar areas with fiscal dimensions. Furthermore, crisis management measures have contributed to moral hazard by raising market expectations of large public financial support, including liquidity injections, in times of stress.

These weaknesses have created an awareness of the need for more formal and better co-ordinated arrangements to deal with financial stability issues, including bank resolution.

At the European level, the financial turmoil exposed the lack of co-ordination in regulation and supervision between national authorities and uneven levels of supervision which complicated crisis management. As mentioned above, the financial crisis also revealed a general underappreciation of systemic risks in micro-prudential supervision and highlighted the need for a more system-wide macro-prudential approach towards supervisory oversight to ensure overall stability in the financial system.

In response, in Europe we see a process of setting up pan-European supervisory authorities to enhance micro-prudential supervision which, among other things, will help co-ordination and harmonise regulatory standards.

The need for strengthening the macro-prudential orientation of financial supervision has led to an important new initiative at the EU level. It was decided by the European Council in June 2009, in line with the de Larosiere (2009) report, to entrust macro-prudential supervision to a new body, the European Systemic Risk Board with the objective of increasing the focus on systemic risk within the framework of financial supervision.

However, there is a third area where efforts lag behind. Despite the serious weaknesses on issues relating to crisis management and the call of the de Larosiere report for "a coherent and workable framework for crisis management in the EU", not much progress has been made towards a comprehensive European crisis framework focusing on early intervention by supervisors, bank resolution and insolvency proceedings.

That said, an opportunity is provided to build up a crisis management framework consistent with the regulatory and supervisory frameworks allowing good co-ordination between policymakers and taking account the potential problems of moral hazard and of the fiscal dimensions of policies of public financial support and liquidity assistance.

The provision of liquidity by central banks to address stresses in systemically important markets can lead to potential moral hazard. Particularly in times of crisis, potential moral hazard can be reduced by the central banks and others having the information and tools on an ongoing basis to be able to identify systemic vulnerabilities, which in turn require continuous monitoring and co-operation with regulators and supervisors. Intervention from the central bank should only be taken when other measures are not available, and if a sustained effort is required to support a particular market then it should be handled by the government as this is a fiscal task.

The greatest difficulty, perhaps, is associated with developing a framework for crisis management involving cross-border financial groups. One approach is for a European resolution authority that could be given the mandate to deal with failing cross-border banks. But controversy surrounds the financing of bank resolution measures and, ultimately, the use of public money to support ailing banks. The Commission has suggested the establishment of bank resolution funds by member states to be funded ex ante by a levy on banks. However, the resolution funds could be used as insurance against failure or to bail out failing banks thus creating a moral hazard problem. To address this problem the Commission has suggested that these funds be used to facilitate an orderly failure (bridge bank, transfer of assets/liabilities, good bank/bad bank split, etc.). However, in devising and timing the least costly resolution measures there would seem to be a need for the resolution authority to be in close cooperation with the supervisory authorities which possess institution specific information. This would be similar to the close co-ordination required between central banks as lenders of last resort and micro-prudential supervisors in providing emergency liquidity assistance to specific financial institutions.

Concluding remarks

During the crisis central banks have been successful in meeting their primary policy challenge of delivering price stability. A robust institutional framework for monetary policy, whereby an independent central bank pursues a clearly defined price stability objective establishing well-anchored inflation expectations, was most instrumental in enabling this success. Furthermore, the sound price stability credentials of central banks provided them with the flexibility to take unconventional monetary policy measures as policy interest rates approached the zero interest rate bound and avoid a deflationary slump reminiscent of the 1930s when monetary policy was passive.

In contrast, the contributions of central banks in meeting the challenge of financial stability have been limited on many occasions by the insufficient competence in regulation and supervision matters pertaining to credit and finance. The ongoing financial crisis with its destabilising effects on segments of financial markets in Europe has intensified the need to improve substantially the architecture for financial stability, in the process paying close attention to coordination between the financial supervision and crisis management aspects with strong involvement of central banks.

As a closing thought, I would stress that financial stability is a global public good. As with any public good, markets cannot be expected to deliver the socially desirable degree of financial stability on their own. But neither can governments in isolation. In a globalised financial environment that transcends national borders, maximum cooperation among government authorities is necessary to arrange for the optimal supply of financial stability. A major challenge ahead is how to improve the European and international architecture of financial supervision towards that end.

-------------------------------------------------------------

REFERENCES:

de Larosiere, Jacques (2009) Report of the High-Level Group on Financial Supervision in the EU, 25 February.

Orphanides, Athanasios (2010) "Monetary policy lessons from the crisis", Central Bank of Cyprus Working Paper 2010-1, May.

FIGURE 1: Inflation and Long-Term Inflation Expectations

Note: HICP shows the rate of increase of the index over 12 months. Expected inflation is the average five-year ahead forecast reported in the ECB SPF. The thin red lines denote the 25th and 75th percentiles and the shaded area reflects the interquartile range of the cross-sectional distribution of the individual responses. Reproduced from Orphanides (2010).