Preparing for the euro: lessons learned and challenges ahead

Remarks by Athanasios Orphanides, Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, on “Perspectives from the Monetary Policy Strategy in Cyprus”

- Contribution to the panel discussion –

Vienna, 19 November 2007

Governor Liebscher, dear friends and colleagues,

It is a pleasure to participate in this conference, the latest in the series of excellent conferences on European economic integration organized by the National Bank of Austria.

With merely 42 days left before the introduction of the euro in Cyprus and Malta, and with the changeover logistics and practical preparations largely completed, I find it especially appropriate to talk about preparing for the euro, the lessons learned and the challenges that remain ahead.

I will take this opportunity to examine the broader issue of monetary policy strategy on the road to the euro and related challenges for euro aspirants.

Many of these challenges and the appropriate monetary policy strategy required to respond to them are likely to be country specific - reflecting the historical experience and institutional arrangements in place long before entry into the euro area. Past experience has shown that there is no unique trajectory for a country’s entry into a monetary union. For this discussion, I will draw upon the experience of my country’s entry into the European Union and preparation for the euro area.

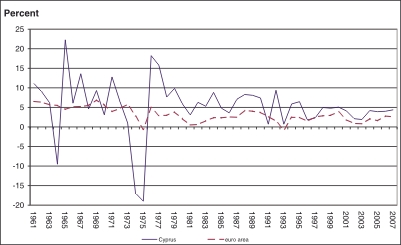

Cyprus has a small, open and services oriented economy. Real GDP growth has been historically robust, averaging around 6% since the island’s independence in 1960 - consistently above the average trend for the euro area as well as for the European Union as a whole (see Figure 1).

Consistent with this robust real GDP growth, the unemployment rate has historically been lower and more stable than in the rest of the European Union (see Figure 2). Indeed, the remarkable stability is noteworthy. An important exception was the period 1974-1975, reflecting the vicious invasion of Cyprus by Turkey in 1974, which displaced one third of the population from their homes making them refugees in their own land. Despite the economic devastation, the Cypriot economy bounced back at an amazing pace.

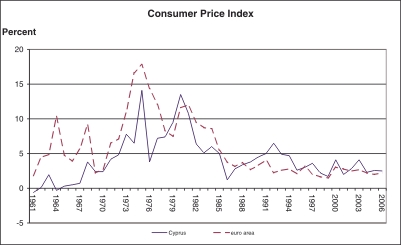

Though one might expect that high economic growth, in conjunction with low unemployment, could lead to higher inflation, this did not materialize in Cyprus. Inflation remained relatively contained throughout the years, an outcome that could be attributed to the prudent monetary and exchange rate policies that had been followed by the Central Bank of Cyprus ever since its foundation in 1963.

Indeed, against the setting of a small and open economy, it was recognised soon after the establishment of the Central Bank in 1963 that targeting the exchange rate would be an appropriate means for achieving the Central Bank’s primary objective of price stability. To the extent that our major trading partners remained committed to price stability, managing the exchange rate by pegging the Cyprus pound to a strong anchor - be it a single currency or a basket of currencies of our main trading partner - could deliver the desired price stability objective. A strong peg would also contribute towards anchoring inflation expectations, thereby alleviating any possible second round effects to temporary shocks, further facilitating the achievement of price stability.

In 1992 the aspiration to join the European Union led to the unilateral peg of the Cyprus pound to the ECU, with the central rate of 1 ECU = £0.585274 and fluctuation margins of ±2.25%. This was an important step in the policy of linking the economy more closely to the economies of the EU, even though the ECU basket did not reflect very well the composition of trade in Cyprus at the time. Similarly, following the establishment of the EMU on 1 January 1999, the Central Bank decided to link the Cyprus pound to the euro with a central rate and margins equal to those of the ECU, despite the fact that the UK, our major trading partner, opted to stay out of the euro area.

In view of the introduction of a new monetary policy framework encompassing market-based instruments in 1996, and especially after the abolition of the statutory interest rate ceiling in 2001, the Bank has been implementing this strategy by setting its interest rates so as to steer short-term and long-term market interest rates towards levels consistent with exchange rate stability.

Ultimately, the pursuit of exchange rate stability was seen as equivalent to the pursuit of price stability. The existence of a sound exchange rate regime, the monitoring of the money supply, liquidity of the banking system and credit to the private sector, as well as the pass through to the current account, have been the key elements of this strategy.

Overall, the monetary policy strategy I have just described has been applied resolutely in a credible and consistent fashion by the Central Bank of Cyprus. The long track record of price stability in Cyprus is the most obvious proof of the success of this strategy.

As can be seen in Figure 3, inflation remained in check, averaging between 2%-3% over the greatest part of the past forty years, with the most notable exception being the experience of the 1970s. Even during that decade, however, inflation in Cyprus largely reflected increased inflation faced by the countries of its anchor currencies, rather than loose monetary policy in Cyprus. This favourable comparison, especially for the second half of the 1970s, is even more remarkable in light of the economic destruction of much of the island’s economy resulting from the invasion and occupation of over one third of the island by Turkey. In retrospect, the experience of Cyprus may serve as an instructive example of the long-term benefits of a monetary policy focused on price stability, even in the presence of dislocations that might have been seen as providing cover for looser, less responsible monetary policy in other contexts.

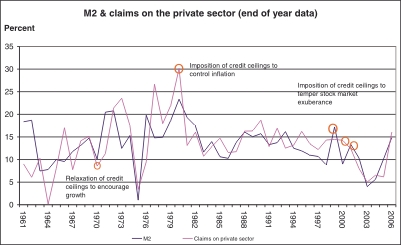

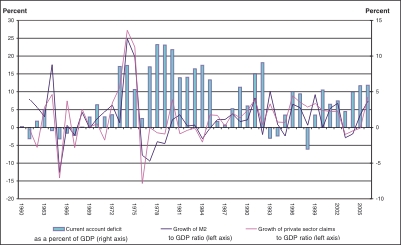

The success of this policy strategy could be attributed to four key elements. The first element of this strategy was the close monitoring of monetary aggregates and credit, in particular credit to the private sector, with a view towards reigning in excessive rates of expansion that might threaten stability. The second element was the close monitoring of the current account deficit, both as an indicator of inflationary pressures and as a warning signal helping to avoid external imbalances.

The third element contributing to the success of this strategy was the safeguarding of the credibility of policy in maintaining a stable currency - stable against a strong anchor - even during periods of quite adverse economic conditions. For a small open economy, second chances to re-establish credibility following a devaluation may not come by as easily as might be desired. Rather, the loss in credibility resulting from a devaluation might be more costly than the short-term benefits the devaluation might bring.

Apart from credibility, however, other economic conditions prevailing in Cyprus at the time precluded the use of the exchange rate as a means of restoring competitiveness. Given the dependence of the economy on imports, any short-term benefits accruing from a devaluation would have been offset by the higher cost of imports and the subsequent rise in prices due to the prevalence of automatic cost of living adjustments (COLA) in wage contracts. In other words, full employment conditions, the existence of COLA, and low price elasticities for the demand for exports and imports (with the sum estimated to be less than unity), meant that a currency devaluation in Cyprus would have brought a worsening of the balance of payments with the higher demand for exports completely offset by the resulting higher increase in imports’ expenditure. Thus, doing what was necessary to maintain external balance and avert the need for devaluation was an important element of the strategy.

In this light, non-traditional policy tools such as capital controls and quantitative credit restraints proved useful supplements to the more traditional tools - and indeed sometimes the crucial main tools - for controlling threats towards imbalances. Hence, the fourth key to success. Non-traditional tools were used with care, however, in order to control and correct imbalances in the short-term, and not to obscure and prolong them. Care was needed, of course, because it was well understood that, when improperly used, controls and restraints can easily engender unsustainable imbalances endangering economic collapse at a later stage.

Figure 4 illustrates the timing of imposition and relaxation of credit ceilings during periods of hardship. The most significant ones occurred in 1967, when credit ceilings were relaxed to encourage growth; in 1980, when credit ceilings were imposed to contain inflationary pressures; and in 2000, when credit ceilings were imposed to contain an episode of stock market exuberance.

This admirable performance should not obscure the various challenges that tested the efficiency of the policy we had in place. During the 1990s a number of EU accession-induced structural and institutional reforms were among these challenges. The reforms included the welcome liberalisation of some prices and, more challenging for the Central Bank, the liberalisation of capital movements and the further deepening of financial intermediation. These changes required quick adjustments and an active policy response by the Central Bank to maintain effective monetary stability.

In January 2001, following the abolition of restrictions on medium-term and long-term borrowing by residents, capital inflows rose significantly as private individuals and firms increased their borrowing in foreign currency, mostly euro, taking advantage of the interest rate differential between euro-denominated and pound–denominated loans (see Figure 5).

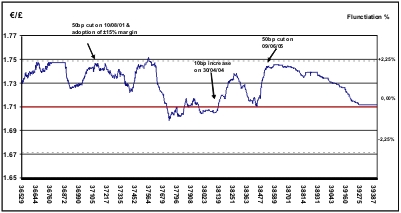

This exerted upward pressure on the exchange rate and it also exposed borrowers to increased exchange rate risks. These developments prompted the Central Bank to abolish the narrow bands of ±2.25% in August 2001, and adopt the wider ±15% margins in line with the ERM II (see Figure 6).

Concurrently, the Bank reduced its interest rates by 50 basis points, a decision that was perceived as being necessary due to the anticipated negative impact of the seemingly prolonged global economic slowdown on the Cyprus economy. The decline in interest rates in Cyprus also reduced the interest rate differential between euro-denominated and pound-denominated loans, which further removed some of the incentive for residents to borrow in foreign currency. Interest rates were subsequently reduced further in September and November 2001 by 50 basis points on each occasion (see Figure 7).

Exchange rate flexibility in concert with prudent interest rate decisions proved instrumental in dealing with the aforementioned challenges.

A smooth transition to full financial liberalisation by May 2004, when Cyprus joined the EU, would have not been possible without timely strategic changes in Bank policy. Three key changes were: (i) the reform of the monetary policy instruments, (ii) the abolition of the statutory interest rate ceiling and (iii) the phased capital account liberalisation. Reference should also be made to the new Law on Banking introduced with a view to reinforcing supervision and enhancing prudential rules.

Overall, the convergence of the financial structures of Cyprus to those prevailing in the EU has been achieved through a carefully planned and gradual reform process. Having in place a well-regulated sound framework proved to be of paramount importance for strengthening the resilience of the banking system and entrenching financial stability against very strong credit expansion, booming asset prices and destabilising capital flows.

In the run-up to the EU accession, the Central Bank of Cyprus had formulated a comprehensive strategy for the adoption of the euro. The overriding objective of this strategy was the adoption of the euro the soonest possible after EU accession. Essentially, this strategy was addressing the issues of when to enter ERM II, what should the central parity be, and how long to stay in the mechanism. After the formation of this strategy, it became evident that the smooth entry and participation in ERM II would be dependant on the prevailing general economic situation and on our success in bringing about the requisite policy adjustments, such as further price liberalisation and a credible fiscal consolidation programme.

Unfortunately, public expenditure outruns and the loose implementation of successive fiscal consolidation programmes resulted in major slippages, with the fiscal deficit surging to 6.3% of GDP in 2003. This, in turn led to increased uncertainty about long-term interest rates. In conjunction with these adverse fiscal conditions, political uncertainty surrounding the prospects for the solution of the Cyprus problem and unfounded rumours concerning imminent devaluation of the Cyprus pound further exacerbated the negative sentiment present at the time. The sizeable capital outflows and the concomitant pressures for currency depreciation in the aftermath of these developments called for increased vigilance by the Central Bank to support the exchange rate. At an extraordinary meeting on the eve of the EU accession day, the Central Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee decided to increase its interest rates by 100 basis points and at the same time to send a strong signal supporting the Cyprus pound. Consequently, markets calmed and capital flows returned to their normal seasonal pattern. In this connection, I should emphasise the success of the Central Bank in properly signalling and communicating its readiness to show policy consistency towards achieving the primary objective. This was imperative to stabilise expectations and avoid recurrent shifts in market perceptions.

Notwithstanding the satisfactory degree of real and nominal convergence achieved by the Cypriot economy, and the implementation of a credible fiscal consolidation programme, challenges also emerged during participation in the ERM II. Following entry into the ERM II, at the same long-standing parity of €1 = £0.585274, sizeable capital inflows were observed, mainly ensuing from enhanced confidence in the Cypriot currency, improved economic outlook and increased residents’ borrowing in foreign currency to take advantage of the favourable interest rate differentials. Taking into account subdued inflationary pressures, the Bank cut its interest rates by a cumulative 100 basis points at two consecutive Monetary Policy Committee meetings.

Moreover, although the fiscal stance was largely supportive during this period, monetary policy was confronted with the dilemma between price and exchange rate stability once inflationary pressures became evident. These pressures were fuelled by surging oil prices and ample banking liquidity that resulted in the sizeable expansion of credit to the private sector. At the same time, excessive capital inflows owing to residents’ increased borrowing in foreign currency were exerting currency appreciation pressures. Reliance on interest rate adjustments on this occasion was not considered as being sufficient to maintain stability. Against this background, the Central Bank embarked on a two-fold strategy encompassing both communication and prudential banking supervision measures.

On the communication side, the Bank offered frequent reminders to the public of the exchange rate risk associated with borrowing in foreign currency. On the prudential side, the Bank issued guidelines reducing the maximum loan to value ratio associated with lending in real estate, and delayed decreases of the minimum reserve ratio to euro area standards.

The decision of the ECOFIN Council on 10 July 2007 to accept Cyprus into the euro area and the concurrent setting of the conversion rate, in one sense marked the completion of the island’s integration into the European family. But it also served as a reminder that controlling inflationary risks in Cyprus may be harder to tackle going forward without further progress on fiscal consolidation and further structural reforms. The historical differential in policy rates between the Central Bank of Cyprus and the European Central Bank will be eliminated by the end of the year, suggesting an easing of monetary conditions at a time when the Cypriot economy is expanding at a brisk pace.

Fast credit expansion, which has been largely directed to the real estate market, continues to be a major concern, particularly because of the increasing exposure of our banks to the real estate sector at the expense of other sectors. With a view towards safeguarding financial stability, the Central Bank called on banks to assess more thoroughly the creditworthiness of loan applicants and further tightened financing conditions by reducing the maximum loan to value ratio for real-estate loans. With these measures, we believe we are facilitating a smoother transition of the Cypriot economy to the euro.

The spectre of an increase in inflation perceptions is yet another risk. As has been the experience elsewhere in Europe, the adoption of the euro is often accompanied by unjustified fears that producers, distributors and retailers may use the opportunity of the changeover to unjustifiably raise prices. Drawing from the experience of countries that joined the euro before us, we have adopted policies, such as a lengthy period of dual pricing and fair pricing agreements to avert this problem.

The recent increases in energy and food prices, however, have complicated our attempts to allay consumer fears. On the energy side, Cyprus is completely dependent on imported oil for all its energy, leaving us particularly vulnerable to recent oil price increases.

Another complication is the prevalence of cost of living adjustments in wage contracts (COLA). Twice a year COLA automatically raises wages by an amount equal to the inflation rate in the CPI over the previous six months. This is on top of any other negotiated wage increases. It is unfortunate that the government has not been able to make progress with regard to this distortionary element in the economy even with civil workers. At present, this unfortunate anachronism risks translating a temporary hump in inflation into a more persistent inflationary threat that may be particularly difficult to counter in light of the easing of monetary conditions associated with our entry into the euro area.

Over the longer run, however, I cannot help but be an optimist. The road towards monetary integration can confront policymakers with numerous challenges whose resolution will depend on the historical experience and institutional arrangements in place, prior to entry into the euro. Despite such challenges, the euro can serve as a powerful catalyst for welcome change, ultimately enhancing welfare not only for countries like Cyprus and Malta that are about to join, but for all European citizens.

FIGURE 1: Real GDP Growth Rate

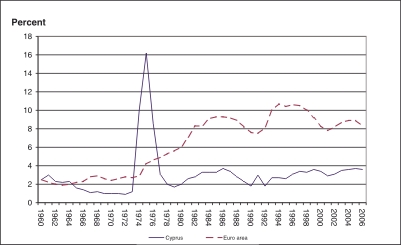

FIGURE 2: Unemployment Rate

FIGURE 3: Inflation

FIGURE 4: Money and Credit

FIGURE 5: Credit and Current Account Deficit

FIGURE 6: Exchange Rate Stability

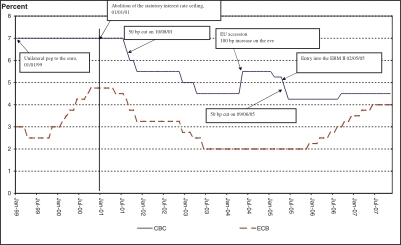

FIGURE 7: Policy Rates